Behind the Mythology: Mermaids

How a 5.000 Years Old Myth Keeps Entertaining Us Today

When it comes to myths and fairy tales regarding the mysteries of the seas and the adventures of brave sailors, mermaids are without a doubt, the favorite antagonists. Charming and beautiful, yet deadly and deceptive, they lure men with their unparallel singing and femme-fatale attitude, leading them to their watery graves, usually by crashing their ships to rocks and then devouring them alive. On the other side, these half-women and half-fish hybrids are often found to be perfect candidates for a romantic yet tragic love story, proving that humans tended to ship human and monster relationships long before “Twilight” came into being…

When it comes to myths and fairy tales regarding the mysteries of the seas and the adventures of brave sailors, mermaids are without a doubt, the favorite antagonists. Charming and beautiful, yet deadly and deceptive, they lure men with their unparallel singing and femme-fatale attitude, leading them to their watery graves, usually by crashing their ships to rocks and then devouring them alive. On the other side, these half-women and half-fish hybrids are often found to be perfect candidates for a romantic yet tragic love story, proving that humans tended to ship human and monster relationships long before “Twilight” came into being…

Mermaids have been around since the rise of the first civilizations on the planet, making them one of the oldest fantasy beings, that keep entertaining and fascinating our brains, even today! You can see them in Harry Potter as slimy fish-people, disgusting nightmarish creatures in Lovecraftian tales of horror, and as seductive, deadly women who try to drown Jack Sparrow at the fourth “Pirates of the Caribbean” movie. Finally, there is the most famous mermaid of all, Ariel, the cute and loving gingerhead princess, which Disney created based on Hans Christian Andersen’s tale “The Little Mermaid”.

Today we’re going to take a trip back in time and witness how these famous creatures were first created, what legends surround them, and why they still manage to capture our imagination.

A Mythical Coctail

When it comes to studying and therefore understanding myths, legends, and religions of old, things can get “foggy” to say the least. This is due to both the lack of written information and because of the abstract nature of the subjects themselves, which in many cases were rewritten, changed, or simply lost in time and replaced by something entirely different. This is the case with the mermaids.

When we imagine a mermaid, we tend to visualize it with its European form. A creature with the upper body of a beautiful woman and the lower body of a fish, who can lure men to their deaths using its beautiful voice, as bait. We tend to believe that the origins of the mermaids are traced to ancient Greece and in a way we are right to believe so. After all, the first historical accounts of mermaids, as described above, belong to Roman authors like Pliny the Elder, who stated in his “Natural History” that not only were mermaids first mentioned in ancient Greece but that they were real and many of them lived in the waters of southern Gaul (Simon, 2014)! However, when we examine Greek mythology, we are left with no information about the existence of such a creature. So, what did happened?

To answer this mystery, we need to trace the roots of ancient Greek mythology, meaning the Mycenaean religion. In the world of the Mycenaenans (the people who inhabited Greece from 3.000 to 1.000 BCE) the Olympian pantheon was completely different from what we know today. Zeus was a simple sky god, while the chief deity was Poseidon, who was the ruler of the Underworld and master of earthquakes and not a sea god! In this pantheon — which seems like a twisted, alternative universe made by Marvel — the title of the “Ruler of the Seas” was held most possibly by Nereus or Oceanus (Greenberg, 2020).

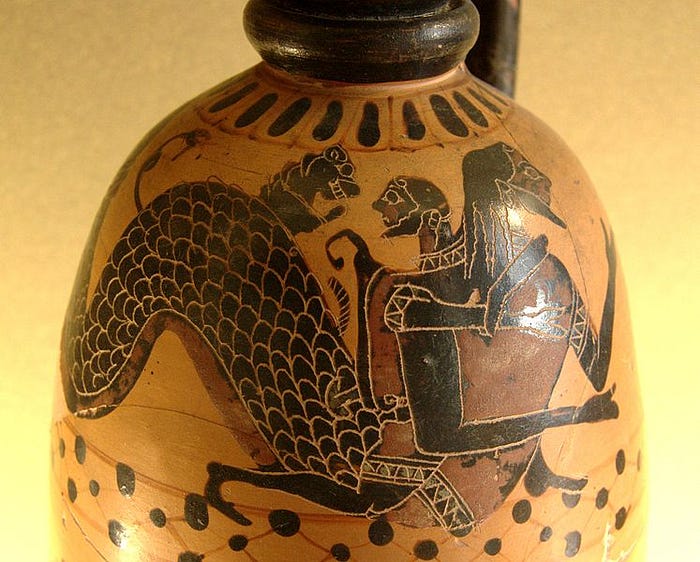

The first one was known as “the old man of the Sea”, or “the sage of the Sea” and was a cthonic deity, who sometimes was also known as Proteus (Greenberg, 2020). Nereus was often depicted as having the upper body of a man and the lower body of a sea serpent or a fish, making him mythology’s first merman. This is the first description of something reminiscent of the modern mermaids. But, why are they still absent?

The answer comes with the 50 daughters that Nereus is said to have, the Nereids. These were water spirits in the form of beautiful young women, known to be extraordinary singers and musicians (Greenberg, 2020). They were protectors of the sea and spent their days playing with marine animals like dolphins, or dancing, singing, and bathing on isolated, well-hidden beaches. Just like their father, they were known to guide sailors who were caught in storms or rescue the ones who were about to drown, and so people often prayed to them for a safe journey, whenever they were forced to travel by ship.

As we can see, the Nereids shared many common elements with the mermaids, including their attractive appearance, playful nature, and tendency to rescue sailors. Overall, the whole benevolent nature of the latter was based on the positive elements of the former. But the Nereids lack two vital characteristics, that the mermaids possess: their fishtails and their thirst for human flesh. Unlike their father, the Nereids were always depicted with full human bodies in Greek art. As for the aforementioned “dark side”, while the Nereids were known to punish the ones who dared to disrespect them, they were in general benevolent deities, who did not murder neither devour humans.

The Scrounge of the Seas

To trace the monstrous appearance and nature of the mermaids we need to turn our attention to other beings of Greek mythology, the “Scrounge of the Seas”, known as the Sirens. Today the words “mermaid” and “Siren” are somewhat synonymous, describing the same creature. But in reality, the Sirens were completely different species of monsters who possessed the body of a bird and a woman’s head (Britannica, 2020). They were one of Greek mythology’s oldest creatures. Originally, before their origin myth was established, there were both male and female Sirens, who guided the souls of the dead to Hades (Elbein, 2018). This, along with their appearance lead historians to believe that they were initially the Greek version of the Egyptian Ba bird — the symbol of the human personality, which was associated with death (Elbein, 2018).

Sirens’ most common origin myth, given by Ovid (Britannica, 2020), goes as follows: They were once the handmaidens of Persephone, who failed to protect her from Hades. In an act of merciless revenge the goddess Demeter — Persephone’s mother — cursed them to forever roam the earth as monsters, seeking eternally their mistress. The Sirens found shelter in a small, rocky island near the sea (the location differs according to various authors, ranging from the Cape Maleas in southern Peloponnese to the Amalfi coast in Italy). From there, sitting on a blossomed meadow filled with human bones, they would lure sailors who happened to pass by with their wonderful voices (Cartwright, 2015).

It is said that listening to the Siren’s song was an otherworldly experience, compared to nothing else. Their angelic, crystal-clear voices sang mourning melodies, which emitted feelings of inevitable death, sorrow, and great danger to anyone unlucky enough to hear them. Like a bittersweet, deadly lullaby, their song bounded the minds of men and drove them insane. Once hearing the Sirens singing, one would instantly cast himself in the sea and start swimming like a maniac towards the monsters. But once reaching the shore, and while still gasping for air, the poor victim would be eaten alive in a matter of seconds, his last screams covered by the sound of the waves and the croaking of seagulls.

The Sirens were famous antagonists in many great stories like “the Argonautica”, “Hercules and the Centaurs of Foloe”, and the “Odyssey”. In the last one, the beasts finally met their demise, when the hero Odysseus became the first person who managed to hear their song and lived. The Sirens were bound with a curse that stated if a mortal managed to resist their song, they would cast themselves into the sea (Cartwright, 2015). Thus ended their reign of terror in the ancient waters.

From Myth to History

In the myth, the existence of the Sirens ended with Odysseus. But in reality, their memory survived and thrived for the next centuries, as we can tell by their presence in countless forms of art from statues and pottery to clay figurines.

There is a simple reason behind this obsession of the ancient Greeks with the Sirens. Since the Bronze Age Collapse of the 12th century and the fall of the great empires in the eastern Mediterranean, new regional powers arose. Seafaring cultures like the Phoenicians, the Greeks, and the Etruscans managed to fill the gap of their predecessors by rediscovering and then expanding the long-forgotten maritime trade routes into unknown waters. In those days the possibilities of surviving such a journey were extremely small. The Sirens represented the unknown dangers that lurked the maritime trade routes. Scholars claim that their song was actually a metaphor for the winds that are known to create a whistle-like sound when passing among the rocky coasts. These “singing winds” would drop the ships to reefs or rocky shores, ending the lives of the sailors in a single moment. It is not a coincidence that the places where according to the myths the island of the Sirens was located were known for their dangerous waters and unpredictable weather. Both the Amalfi coast and the Cape Maleas were avoided for these reasons.

It was because of these very real and dangerous elements, which the Sirens represented, that made them a popular antagonist in every seafaring tale and thus managed to survive in the upcoming centuries.

Mermaids and Medieval Europe

After the fall of the Persian Empire in 334 B.C.E and the rise of the Hellenistic Era, an interesting change takes place. The Sirens lost their feathered bodies! Instead, they began to be represented as beautiful women with the tail of a fish, exactly how the modern mermaids are known to be depicted. We are not sure why such a change took place. Most likely it was the result of a merging that took place when the Greeks witnessed the depictions of the Mesopotamian goddess Atargatis, who according to an Assyrian myth casted herself into the sea, and her lower body transformed to a fishtail, after the loss of her lover (Simon, 2014). These images along with other representations of Mesopotamian deities in a half-fish and half-human form gave birth to the mermaid image that we all know and love today.

This new version of the Sirens passed down from the Hellenistic kingdoms to the Romans and when their own empire finally collapsed, it reached the rest of medieval Europe, where it became widely successful. It is worth noting that the surviving Roman sources mention the creatures not with their original greek name “Σειρήνες”, but with its Latinized version, the world “Siren”. In contrast, the earliest medieval reference to the same creatures comes from England and mentions the name “merewiff” from the Old English words “mere” and “wiff” meaning “sea” and “girl”. It is from this name that we finally get to the world “mermaid”. It is evident that, while the general knowledge of the Roman era, regarding the creature’s name, was lost, their tales survived.

In medieval Europe, mermaids became one of the most famous monsters depicted in bestiaries. Of course, being practically naked women, who used their charming voices and beautiful faces to lure men to their deaths, it comes to no surprise that the Catholic Church associated them with the sin of lust and the evil sexual nature of women, who were viewed as the weaker sex (Hokin, 2018). Basically, medieval mermaids were a bunch of horny, devil-worshipping fish-women, who used their beauty to drag men into lustful acts and murder them, once they got their needed sexual satisfaction.

Epilogue

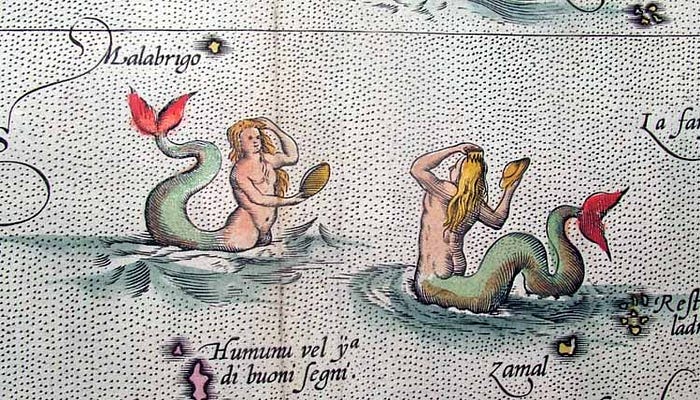

Since the Middle Ages, there have been lots of sailors who said to have seen a mermaid swimming in the vast waters of the Ocean. Amongst the most famous people who claimed to witness the creature was Colombus who is said to have seen mermaids on the coasts of the Caribbean. These could have been the infamous Iara — an exotic version of the European mermaid, present in the tales of the native tribes, or simply a manatee, the slow-moving, seaweed loving “sea cow”, which (in a combination of complete intoxication by alcohol and the effects of water reflection) might the sailors mistakenly thought was a mermaid (Simon, 2014). Considering the fact that Colombus managed to mistake an entire continent for India, we should put our bets on the second option…

From the 16th century onwards the myth of the mermaid exploded, mainly due to the rediscovery of the ancient greek and roman heritage and the exploration of new continents during the “Age of Discovery” (Simon, 2014). Mermaids were carved on the ship’s fronts, became mascots of many taverns, towns, and ports, and were featured in a plethora of tales and legends. They were seen swimming near the ships or devouring men who were unlucky enough to shipwreck when sailing to unknown waters. The rise of European Romanticism in combination with the advance of seafaring technology, which greatly reduced the risks of sea traveling, gave birth to a more romanticized, mild version of the mermaids. This version, which finally reached us, the modern-day audiences, was a hybrid between the sinister Sirens and the benevolent Nereids of Greek mythology, which were mentioned in the beginning.

Mermaids possessed now a gentle side. They were rescuing sailors, who were caught in storms. Other times they even fell in love with them, and this gave rise to many astonishing love stories. Painters and poets imagined them living in utopian marine paradises, where their singing and happiness did not omen the devouring of human flesh.

To conclude, there are many reasons why mermaids remain one of the most famous and lovable fantasy creatures. Their tale is indeed an incredible one, filled with various influences from different cultures and time periods. From servants associated with death to malicious creatures of the sea to devilish femme fatales, and finally sweet and gentle water beings, they incarnate every positive and negative aspect of human nature. Vicious yet gracious, sinister yet benevolent, lustful yet romantic. Just like the ocean, wild, untamable, and unpredictable they truly are a manifestation of human personality, like their ancestors, the Ba birds, were almost 5000 years ago…

Bibliography

Elbein, A., (2018), Sirens of Greek Myth Were Bird-Women, Not Mermaids, available at https://www.audubon.org/news/sirens-greek-myth-were-bird-women-not-mermaids, (last access: 29/10/2021)

Muscato, C., What is a Siren in Greek Mythology? — Definition & Story, available at https://study.com/academy/lesson/what-is-a-siren-in-greek-mythology-definition-story.html, (last access: 29/10/2021)

Greenberg, M, (2020), Nereids: A Complete Guide to the Myth of the Water Nymph, available at https://mythologysource.com/nereids-water-nymphs/, (last access: 29/10/2021)

Encyclopaedia Britannica, (2020), Siren, available at https://www.britannica.com/topic/Siren-Greek-mythology, (last access: 29/10/2021)

Cartwright, M., (2015), Siren, available at https://www.worldhistory.org/Siren/, (last access: 29/10/2021)

Simon, M., (2014), Fantastically Wrong: The Murderous, Sometimes Sexy History of the Mermaid, available at https://www.wired.com/2014/10/fantastically-wrong-strange-murderous-sometimes-sexy-history-mermaid/, (last access: 29/10/2021)

Radford, B., (2017), Mermaids & Mermen: Facts & Legends, available at https://www.livescience.com/39882-mermaid.html, (last access: 29/10/2021)

Hokin, C., (2018), A Short History of Mermaids by Catherine Hokin, available at http://the-history-girls.blogspot.com/2018/05/a-short-history-of-mermaids-by.html, (last access: 29/10/2021)